The Third Battle of Ypres, commonly known as the Battle of Passchendaele, was one of the bloodiest battles fought on the Western Front during the First World War.

Ypres was at the centre of the Allied presence in Belgium for most of the war. In October and November 1914, British and French forces stopped the German advance to the Channel on the high ground east of the city, creating a salient where Allied lines projected into enemy-held territory.

The Allied defence against a German attack in the spring of 1915 became known as the Second Battle of Ypres. For the next two years, trench raids, sniping and artillery fire continued day after day with thousands of men being killed or wounded every month.

At the end of July 1917, the Allies launched the Third Battle of Ypres. Its objective was to take the high ground and break out towards the vital railhead at Roulers, five miles to the east, and the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast.

The attack on 31 July 1917, had been preceded by an artillery bombardment for fifteen days in which four million shells were fired. After some initial success, including the capture of The Pilkem Ridge, the advance made little progress and casualties soon began to mount.

To make matters worse, and just as the Germans started their own artillery bombardment against the attacking troops, it began to pour with rain. In what turned out to be one of the wettest summers in living memory, the battlefield turned into a sea of mud, and as millions of artillery shells rained down, the ground turned into a muddy moonscape that men, mules, guns and tanks disappeared into.

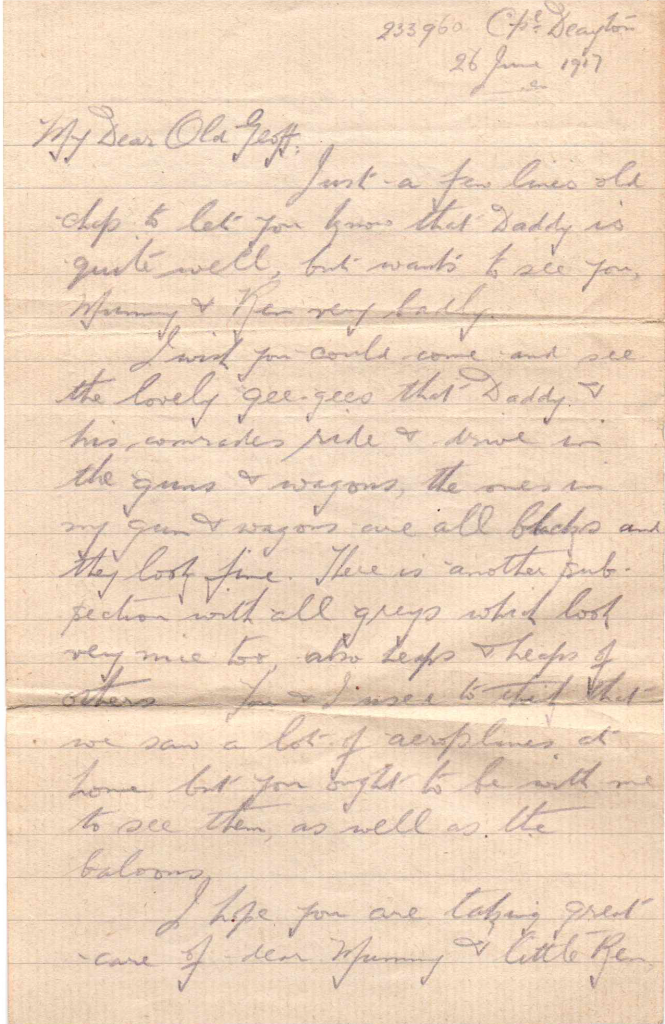

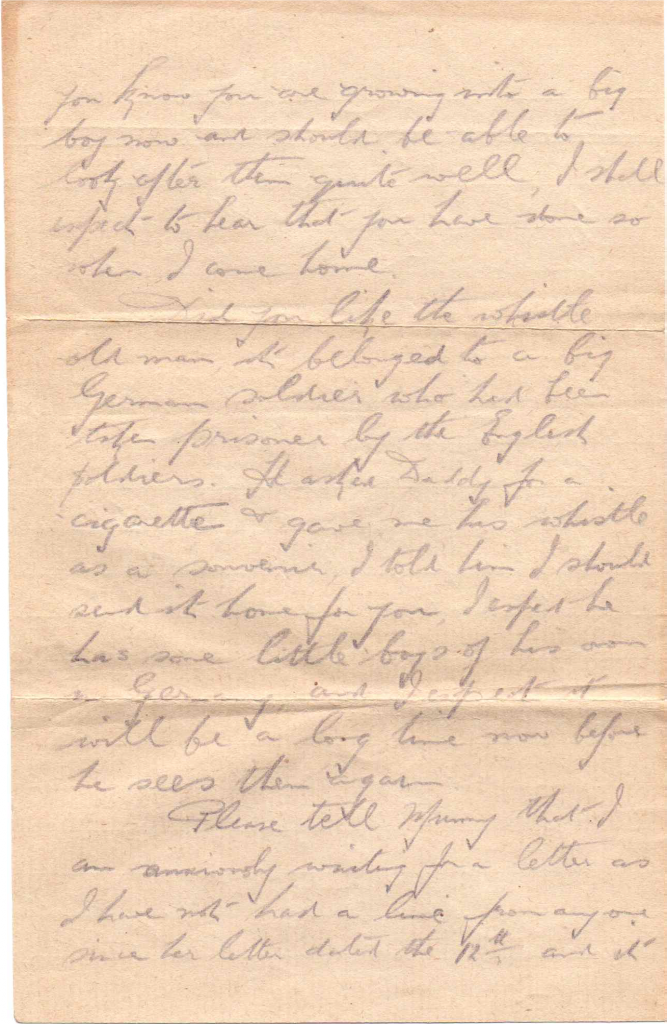

Corporal George Deayton

In the weeks leading up to the Third Battle of Ypres, Corporal George Deayton, a former amateur jockey from Watford, serving in ‘F’ Sub-Section, ‘A’ Battery, 103rd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, describes the scene in a letter to his four-year-old son Geoff:

“My Dear Old Geoff,

Just a few lines old chap to let you know that Daddy is quite well, but wants to see you, Mummy and Ken (his two-year-old son) very badly.

I wish you could see the lovely gee-gee’s that Daddy and his comrades ride and drive in the guns and wagons, the ones in my gun and wagons are all blacks and they look fine. There is another sub-section with all greys which look very nice too, also heaps and heaps of others. You and I used to think we saw a lot of aeroplanes at home but you ought to be with me to see them, as well as the balloons.”

“What is the weather like at home? It is pouring with rain here and the horses are getting a proper shower bath too, still they do not seem to mind it too much. This rain makes it frightfully muddy out here, as the soil is different to ours and does not drain quickly.”

George continues, and gives an insight into the mutual respect so often shared between soldiers in opposing armies:

“Did you like the whistle old man, it belonged to a big German soldier who had been taken prisoner by the English soldiers. He asked Daddy for a cigarette and gave me his whistle as a souvenir. I said I should send it home for you. I expect he has some little boys of his own in Germany and I expect it will be a long time now before he sees them again.”

Ominously George offers a word a word of warning to a previously injured relative:

“Is Auntie Maude still with you and have you seen Uncle Arthur recently? I hope his leg is better now and that he gets home often.

I hope he doesn’t have to come out here again, it is getting a bit too lively to be healthy now.”

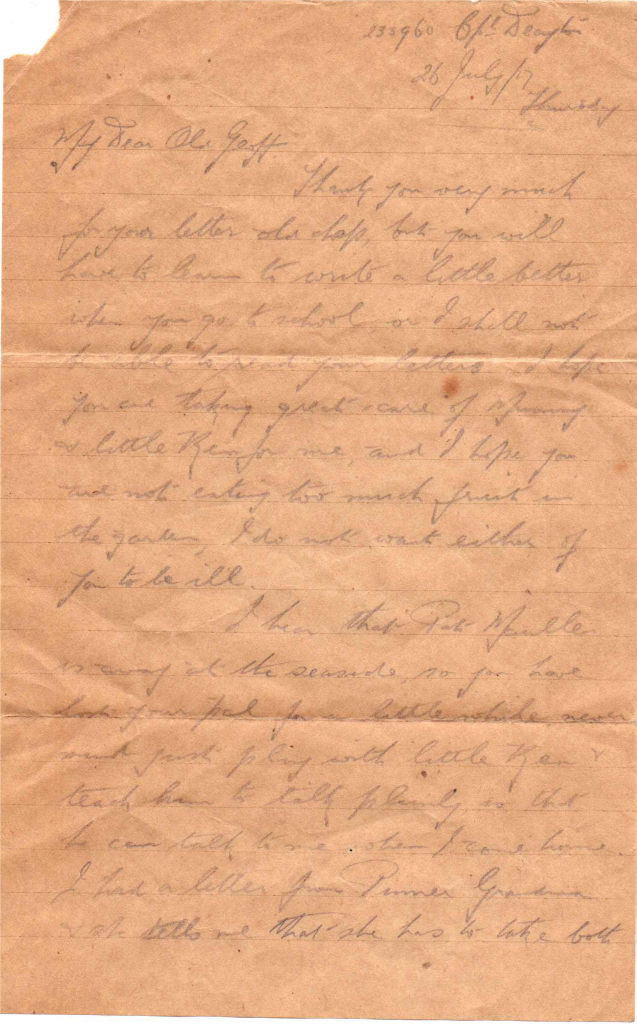

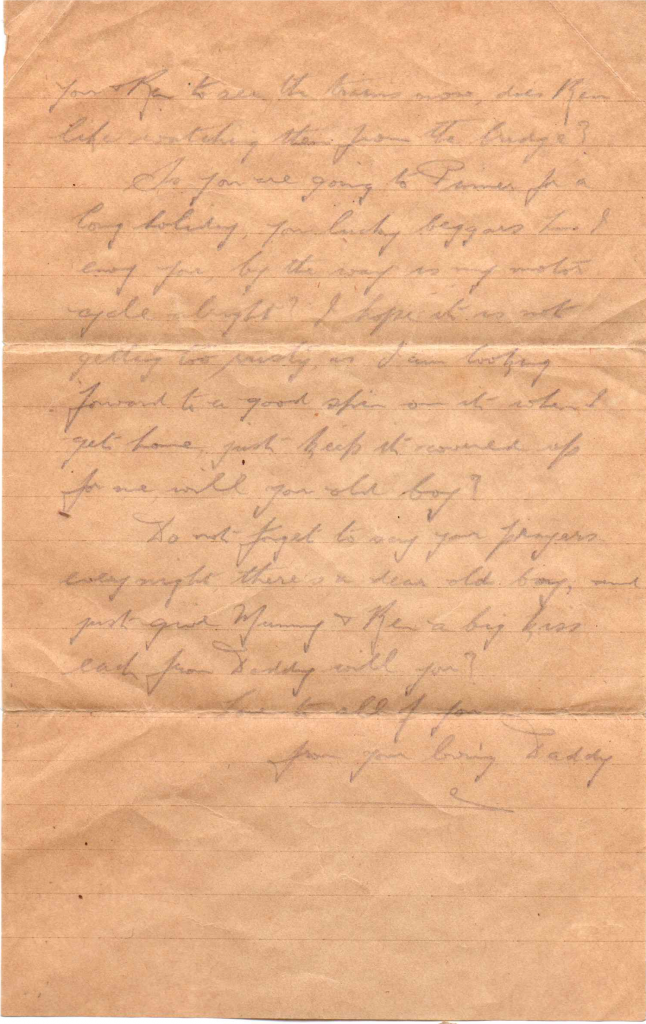

George Deayton letter from the Western Front June 1917:

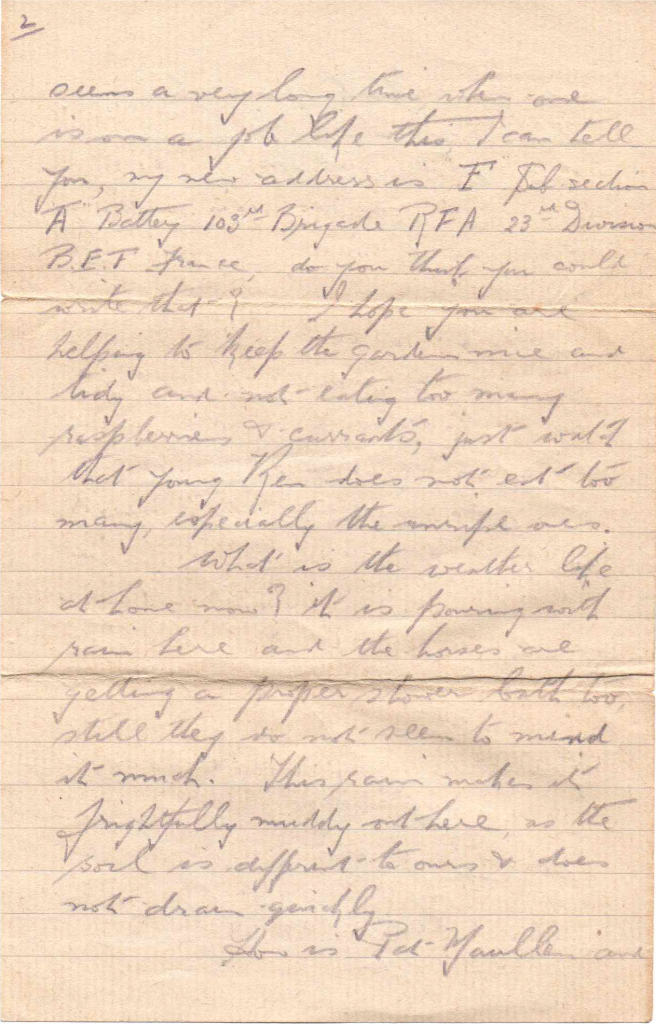

In a letter dated 26 July 1917 (below), just four days before the assault went in, George wrote to young Geoff again and was clearly looking forward to getting out of the Flanders mud:

“My Dear old Geoff

So you are going to Pinner for a long holiday, you lucky beggars, how I envy you, by the way is my motor cycle alright? I hope it is not getting too rusty as I am looking forward to a good spin round when I get home, just keep it covered up for me will you old boy?

Don’t forget to say your prayers every night, there’s a dear old boy, and just give Mummy and Ken a big kiss each from Daddy will you?

Love to all of you,

From your loving Daddy”

Sadly, that would be the last letter that George would send home. While helping a wounded comrade he was shot in the leg. Thinking his fellow gunner was worse off than him, he unselfishly told the medics to deal with his mate first. But tragically for George the bullet had hit his femoral artery and he lost too much blood. His death certificate states that while in the 55th Field Ambulance he died from wounds received in action while serving with the British Expiditionary Force on 10 August 1917, aged 30 years.

Corporal George Deayton was one of an estimated 275,000 British casualties killed, wounded or missing during the Passchendaele offensive. He is buried at Aeroplane Cemetery, 3.5 kilometres north-east of Ypres.

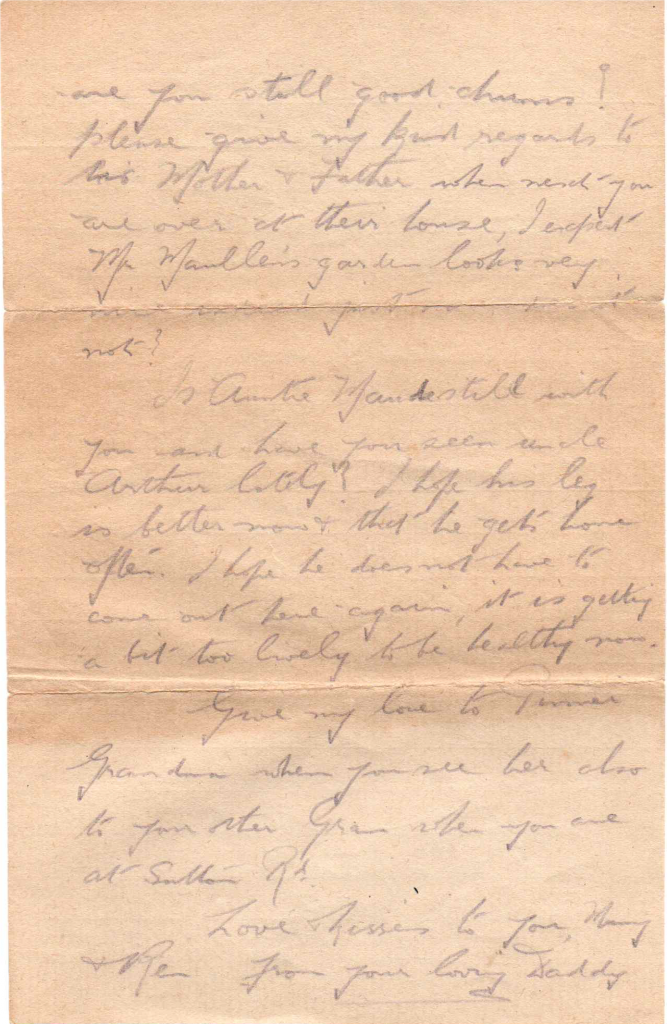

As for Dear Old Geoff and little Ken, well they followed their heroic Dad into service for King and Country during the Second World War. Geoff joined the Royal Artillery, was commissioned in 1943, and saw action in North Africa and Italy. Ken enlisted in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps before volunteering for the Commandos, rose to the rank of sergeant-major, and saw action in the Middle East and North Africa.

Ken and Geoff Deayton (3rd and 4th on right).

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to George Deayton’s family for providing letters, photographs and for allowing me to share his story.

Other sources:

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Imperial War Museum

Follow | Subscribe | Buy

Your name Mcharg attractive be my attention. John Mcharg and I worked together to research our warehouse memorial in the Village of Crosshouse near Kilmarnock. Ours is still a work in progress but the basic stories are similar and relevant. We produced a booklet which I would be pleased to send you.

Thank you again Ian, I visit this account of my Grandfather’s life and death often. It still brings tears to my eyes.